Davy Crockett, Politician

We are bringing Congressman Davy – a new musical about Davy Crockett's political career – to a wider public for America's Semiquincentennial in 2026. Find out how you can help!

The immense gap between the reality and legend of Davy Crockett first snapped into focus in 1835 – the year before his untimely death as a defender of the Alamo.

Crockett was already a walking, talking tall tale. The Almanacks that fueled his posthumous fame in the 19th Century were already being published without his input or permission. His lofty national profile and open disdain for President Andrew Jackson (and his own Democratic Party) led the opposition Whigs to court him as their 1836 presidential candidate.

Yet hard truths awaited Crockett back home in Tennessee. Longtime antagonist Adam Huntsman – a savvy lawyer with a peg leg acquired fighting in wars against the Creek Indians two decades before – entered the race against him in the state’s 12th Congressional District.

West Tennessee politicking in this era was a brusque admixture of dirty tricks, outright slanders and intense faction, washed down with whiskey at barbecues. So Crockett and Huntsman brawled their way across the district in summer of 1835.

Huntsman was a formidable foe. His Biblically-inspired satire on Crockett had achieved notoriety a few years earlier. Crockett branded him a “poor little possum headed lawyer,” adding by way of explanation that: “I have cut open many possum’s [sic] heads to hunt for brains and I never found any …”

When the votes were counted, Crockett lost by a mere 252 votes out of 9,502 cast. He was furious, and claimed that he had been “rascalled out” of victory. He reportedly mocked Huntsman as a “Timber Toe.”

So Crockett decided to cast his own vote on US politics with his feet – and lashed out as his own constituents as he left:

In my last canvass, I told the people of my District, that, if they saw fit to re-elect me, I would serve them as faithfully as I had done; but if not, the might go to hell, and I would go to Texas. I was beaten, gentlemen, and here I am.

We all know how that trip turned out. Yet theories of how Crockett died at the Alamo remain bitterly contested. Some researchers argue that he perished in a predawn onslaught launched against the rickety fort by Mexican President Antonio López de Santa Anna. Others believe that Crockett was among six survivors executed on Santa Anna's orders in the courtyard of the now-blasted mission.

However Crockett died on March 6, 1836, the immortality he won in that famous defeat was rooted partly in his own naked anger about a lost election.

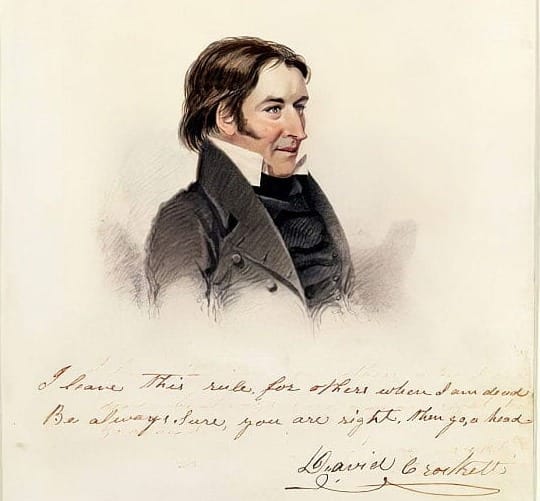

Distinguishing the real Davy Crockett from the legend is a frustrating task. The paper trail is surprisingly thin for a very public man who served three terms in the U.S. House of Representatives. Yet the researchers who have gathered tangible facts about his life and career have found a man at the center of the fractious and bitter politicking of America’s Jacksonian era.

Tracking down Crockett the man took over a century. Only at the height of a new wave of Crockettmania created by Walt Disney’s King of the Wild Frontier television series in the 1950s did James Atkins Shackford publish the first comprehensive Crockett biography. David Crockett: The Man and the Legend chased down elusive evidence to fashion a portrait of an all-too-human figure behind the tall tales.

Davy Crockett’s political trajectory from local justice of the peace to Congress was at the center of the story. After a first failed bid for the U.S. Congress in 1825, he won office in 1827 on a platform of land reform. A number of his constituents had squatted upon (and farmed) disputed lands in central and Western Tennessee, but their efforts to obtain title to their homesteads were frustrated at both the state and federal level.

Crockett promised a solution. Yet bitter squabbles with fellow Tennessee legislator (and future President) James Polk and other Democratic allies of Jackson over what sort of relief bill split the state’s politicians. Left empty-handed, Crockett veered from a vaguely pro-Jackson stance to outright opposition of Old Hickory by the early 1830s.

An 1834 Crockett speech offers a taste of these sentiments:

I was one of the first men that fired a gun under Andrew Jackson. I helped to throw around him that blaze of glory, that is blasting and blighting every thing it comes in contact with. I know I have equal rights with him, and so has every man that is not a slave; and when he is violating the constitution and the laws, I will oppose him, let the consequences to me be what they may.

Such voluble attacks on Jackson (as well as his failure to deliver reforms) cost him his seat in Congress in 1831. Yet Crockett’s reputation only grew in political exile. A play based on his persona called Lion of the West sold out theatres after its April 1831 debut in New York City. An unauthorized biography published in 1833 flew off the shelves so quickly that Crockett eventually wrote his own memoirs (A Narrative of the Life of David Crockett By Himself) a year later.

So when Crockett squeaked back into Congress in 1833, he arrived in the nation's capital (then known as "Washington City") more famous than ever. He was also spoiling for a fight. The opposition Whig Party noticed, and it courted him as a potential ally by organizing a raucous and lavishly-funded Crockett tour of Northeastern states in 1834.

The problem? Congress was in session as Crockett took bows from roaring crowds. His absences didn’t go over well with Tennessee voters. They voted him out again in 1835.

Shackford took the view that Crockett was a political naïf exploited by the Whigs. This notion persisted for decades, until James R. Boylston and Allen J. Wiener published their richly-nuanced study: David Crockett in Congress: The Rise and Fall of the Poor Man’s Friend (2009).

Boylston and Weiner's work was rooted in voluminous primary source evidence, including correspondence, journalism and political circulars. They made the case that Crockett was a principled actor in a fractious political moment. Not only did he seek land reform, but he openly opposed Jackson’s War on the Second Bank of the United States, as well as the Indian Removal Act of 1830. (The latter measure led directly to the mass deaths among Cherokee peoples on the infamous “Trail of Tears” march.)

The authors argued that Crockett’s dalliance with the Whigs was a marriage of mutual connivance and convenience. Frayed relations with the Tennessee delegation meant Crockett sought a wider alliance for land reform. The Whigs needed a frontier philosopher to broaden their own electoral appeal.

“Rather than a simple-minded pawn in the hands of more adept politician,” Boylston and Wiener write, “[Crockett] was a staunch activist for his agenda and allied himself with those who shared his views.”

In a notebook entry from 1831, Alexis de Tocqueville remarked that by electing Davy Crockett to Congress, Tennesseans had chosen a man who “has no education, can read with difficulty, has no property, no fixed residence, but passes his life hunting, selling his game to live, and dwelling continuously in the woods.”

This verdict from the author of the classic Democracy in America survived for over a century. Shackford and Boylston and Wiener upended it and replaced it with the notion that Crockett's topsy-turvy career mirrored the era’s political tumult.

Yet discovering that Crockett's bumptious bumpkin persona hid a conscientious and canny operator with a fierce independent streak elides one fundamental question: Why was this legendary frontiersman such a sore loser when it came to politics?

The Crockett mythos is rooted in positive qualities: optimism, self-reliance, and self-deprecating wit. Yet his nasty disposition in defeat was not confined to that single close election in 1835. It is behavior with startlingly familiar contemporary parallels.

Take Crockett’s narrow loss to Tennessee lawyer William Fitzgerald by 586 votes in 1831. Entangled in a dirty campaign that he felt he was losing, Crockett turned up the personal invective against both Fitzgerald and Andrew Jackson.

After the ballots were counted, Boylston and Wiener observed that Crockett complained that was bested by “managemint [sic] and rascality.” He branded Fitzgerald as a “perfect lick spittle,” and would not even utter his name, preferring to call him “the thing that had the name of beating me.”

Crockett briefly tried to contest the final results of the 1831 election as well.

Political pique and self-pity was also at the center of the 1835 defeat that led Crockett to tell his constituents to “go to hell.” In a letter to his publishers, he wrote that “I have suffered myself to be politically Sacrafised [sic] to save my country from ruin & disgrace…” Crockett insisted in another missive that “Santa Ana’s Kingdom will be a paradise, compared to this, in a few years.”

The ironies of Crockett’s tragic Texas journey are profound. The ruler of the “paradise” he sought in Texas may have ordered his brutal execution. But his untimely and unhappy death was transformed into a glorious and enduring American legend.

A deeper irony? His son, John Wesley Crockett, became a Whig and successfully finished the political work that had left Crockett vituperative and embittered. John Wesley first won election to his father’s seat in 1837, trouncing his opponent, Archelaus M. Hughes. (His father's nemesis, Adam Huntsman, had declined to run for reelection.) Boylston and Wiener noted in David Crockett in Congress that John Wesley worked on a bipartisan measure with a Democratic legislator that won land reform for the citizens of West Tennessee at last in 1841.

So while Davy Crockett's sour grapes likely cost him his life, the Crockett clan won out in the end – on Tennessee’s frontier, in Congress, and, of course, in American history.

Not a subscriber to Stage Write? Sign up here. It's free – and it will stay that way.

Read more about my work at my website.