Not So Wonderful Things

An essay by Richard Byrne.

I went to the Smithsonian Institution’s Archive of American Art on September 2, 2025. My friend and colleague Jarett Kobek asked me to do so in late August, when he saw an online auction listing.

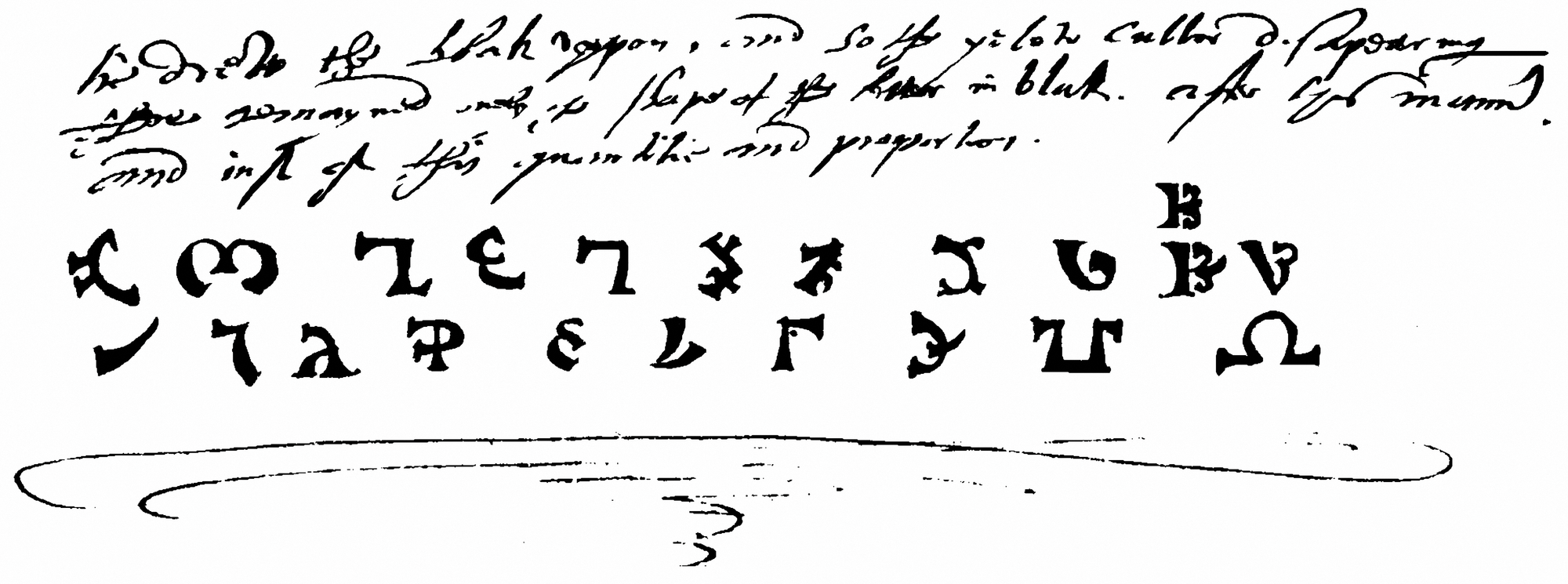

Jim Sanborn, the creator of the Kryptos statue on the grounds at CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia, was selling the solution to the long-unsolved fourth strand of a code (K4) that was embedded in the artwork.

The web page announcing the auction noted that “One bidder alone will acquire what Sanborn alone has possessed since 1990: the complete solution to Kryptos.” Among the items listed for sale? “Copies of coding charts used to code Kryptos (originals at the Smithsonian), 4 pieces.”

I made an appointment to look at Sanborn’s public files, and spent a few hours examining them. I copied relevant images to send to Kobek in Los Angeles that evening.

Kobek called me after he looked through the photos.

In combination with the public clues about K4 released over the past decade by the artist himself, a few of those images allowed Kobek to recover the plaintext – or decoded message – of one of the world’s most intractable codes.

This revelation came – as happens with so many difficult codes – though human error, not raw cryptology.

Cue the whirlwind. We found ourselves in a bitter fight centered on secrecy and power – and their impact on our freedom to research and discover.

This story has been told on the front pages of two major newspapers now. (We laid it out fully in a joint interview with Zona Motel.)

The reaction of Sanborn and the auction house to our discovery has been intense. Offers of auction proceeds. Demands that we sign non-disclosure agreements (NDAs). Then public dismissals of the importance of our findings.

Yet we have not had an opportunity to lay bare precisely why we categorically rejected the seller/artist’s initial offer of money for our silence. Nor have we stated why we said “no” to signing NDAs: first with Sanborn, and then a month later with the seller and the auction house.

The published record is clear. We didn’t ask for anything. We didn’t want anything. We didn’t take anything. We got in touch directly with the artist. We explained what we had done and shared the relevant images with him. Our sole expectation was that the auction would be revised to reflect the new circumstances created on September 2.

It quickly became clear that this would not be the case. Indeed, Sanborn used the information we provided to him to seal parts of his archive from public view for decades.

Our “no” to money and the NDAs was anchored in our own views of transparency and power. These views were plainly at odds with those of both the seller in early September – and the auction house weeks later.

A clash that we did not seek became inevitable.

Our startling impasse with Sanborn led us to get in touch with John Schwartz – a former New York Times journalist who is the dean of the Kryptos beat in American journalism. We were anxious about the auction going forward without any disclosure of what had transpired. And we knew that Schwartz was the reporter who had broken every major K4 story.

The New York Times worked on a piece about the recovery throughout September and early October without publishing it. Suddenly, on the evening of October 8, the auction house’s lawyers emailed cease and desist letters to Kobek and myself.

These missives warned us against disseminating the recovered plaintext and threatened legal action against us. (The deputy general counsel of The New York Times was copied on these letters.)

Once we had obtained counsel ourselves, we learned through them that the auction house had nothing new to ask, but only lodged renewed demands that we sign the same sort of non-disclosure agreements we had rejected weeks before.

In the end, we did not do so. Sanborn’s auction went live on Thursday, October 16 with a disclosure of our use of library science to recover the plaintext.

The Times published its piece at last that same morning. It was on the front page of the next day’s print edition.

For decades, Jim Sanborn has made a public game of decoding the four ciphers he had embedded into Kryptos. This makes sense. It is a work of public art that was paid for by U.S. taxpayers and installed on the campus of the Central Intelligence Agency in Langley, Virginia, in 1990.

Sanborn celebrated those who cracked the first three ciphers via cryptology. But the persistent insolubility of K4 by those methods over ensuing decades has led him to offer significant clues to the final code. He also has demanded a $50 fee to vet proposed answers.

Dozens of proposed plaintext recoveries have been posted online by eager solvers. Kobek simply could have done the same. Put it up and let a community of researchers sort it out. We chose to be ethical and empathetic and wholly transparent.

One certainly can chalk up some of the subsequent rancor to inconvenient timing. Yet the materials I copied were available in a public archive for more than a year – perhaps two – before we happened upon them. We would never have thought to go to the Smithsonian in the first place without the auction house’s listing.

It is clear to me only now that a broader collision of principles and world views was unavoidable.

I remember being astounded – even before I visited the archives – by a phrase attributed to the seller on the auction website: “The secret passes from artist to keeper.”

Sure, this is claptrap. After all, the artist still knows. But this formulation and subsequent statements reveal something profound: a deep preoccupation with secrets, as well as with wielding the power associated with them.

Sanborn’s open letter announcing his decision to sell the solution was blunt:

Power resides with a secret, not without it .

He amplified this notion in contemporaneous news coverage:

“The power is in the secret,” he said. “Without the secret, you have no power.” (New York Times, August 4, 2025)

“If you don't have the secrets, you don't have any power.” (Wired, August 15, 2025)

The executive vice president of the auction house, Bobby Livingston, sounded a similar note in the same New York Times story quoted above:

“Knowing the secret and being the only person who has the secret is where the value lies.”

These statements make clear why Jarett Kobek and myself have found ourselves at the business end of so much unpleasantness, harassment, and expense.

Of course my trip to the archive on Kobek’s behalf was bad timing for Sanborn and the auction house. Yet something deeper was at stake: a significant diminution of the seller/artist’s power.

And when your response to this turn of events is to summon promises of cash, to make demands to sign nondisclosure agreements, and to issue a welter of “legal communications” (as the Washington Post put it) to protect the power of your secret?

One sees how readily such a world view can veer into suppression and malignancy.

As writers and researchers who spend a lot of time in archives poring through documents, Kobek and myself obviously take a different view.

Our practice works in profound opposition to Sanborn’s present assertions about Kryptos and what is valuable about it. We enter archives to excavate and illuminate. We seek to discover knowledge and to advance it.

We certainly don’t do so in order to seal up what we find as one might seal up a tomb.

It also means that we cannot embrace what Kryptos has become in this moment: a toxic intersection of secrecy and commodity.

Is it any wonder we said no?

This was not always the case, of course. Lay aside the code for a moment. The story of how Sanborn actually made the object called Kryptos in the late 1980s is an engrossing parable on the interaction between public art and American state power.

As a dramatist, I recognize readily that this story would make a terrific script. A struggle to shape resistant and difficult materials to realize one’s vision in contested space. Responses to your work that range from incomprehension to skepticism to ridicule. Keeping the difficult balance required to square one’s personal inspiration with the demands of public funding and state security.

As our own ordeal with Kryptos has unfolded, I have thought often about its decoded K3 strand, which quotes Howard Carter’s account of the opening of King Tutankhamen’s tomb in 1922. It is a segment that leaves the reader on the cusp of the archaeologist’s declaration of what he saw inside:

“Wonderful things.”

How far we find ourselves from that vision of Kryptos in this present moment.

Perhaps the wonders of discovery are evanescent. Recent news accounts have revealed that the tomb opened by Carter in 1922 might be on the verge of collapse. A new study argues that floods have compromised its structure significantly.

Yet Kobek and myself have wagered our time, tumult, and treasure to argue that this vision can be sustained somehow. And also to maintain our freedom to ask more questions. Dig deeper.

Writers possess power as well. A commitment to tell a story and tell it straight confers the power to refuse to sell your silence. It also means that you can say “no” to any insistence that you surrender your story at (metaphorical) gunpoint.

In a perilous moment when citizens in this country are rediscovering and embracing their own power to say “no,” our choice to do so in much less exigent circumstances proved surprisingly straightforward.

We also see it as a reminder that we all possess such power. Even now.

Not a subscriber to Stage Write? Sign up here. It's free – and will stay that way.

Read more about my work at my website.